Blood feuds have long captured the American imagination, and the abundance of films, TV series, books and songs on the topic bear witness to this enduring fascination. There is certainly no shortage of historical material, as the history of the United States is rife with feuds familial, political and personal. From the desperados and sheriffs of the Old West to two of the young nation’s most important politicians, a wide range of characters in American history and folklore have found it necessary to settle their differences through bloodshed. Election day brawls, “kidnapped” wives and Civil War hostilities that refused to die long after the surrender at Appomattox are just a few of the root causes of our country’s most iconic feuds. Read on to discover 15 of the deadliest blood feuds in United States history.

15. Burr-Hamilton Feud

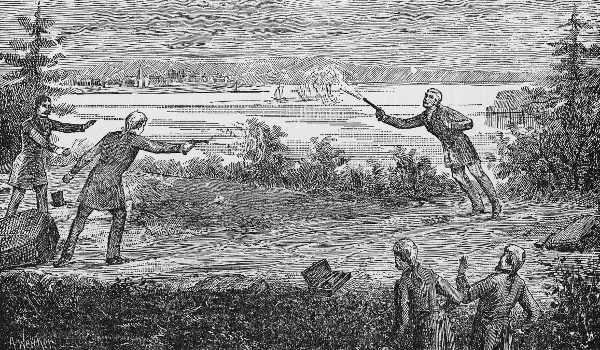

Today’s political sparring and spats have nothing on the Burr-Hamilton feud, a political rivalry that culminated in a deadly duel. The final showdown took place on July 11, 1804, but the enmity between two of the young American Republic’s most prominent politicians has been a long time in the making. Founding Father Alexander Hamilton and sitting vice president Burr had been trading political blows, public accusations and verbal and written insults since 1791.

In 1804, Burr demanded an apology from Hamilton for an affront to his honor, and when Hamilton refused to proffer one, Burr challenged him to a duel. Hamilton accepted the challenge, but his intentions have always been a subject of controversy. His son had been killed in a duel a few years previously, and in a letter written on the eve of his own gunfight with Burr, Hamilton wrote that he had “resolved…to throw away my shot.”

In the early morning hours of July 11, Burr and Hamilton boarded separate boats and rowed across the Hudson River to the Heights of Weehawken, New Jersey. A little after 7 a.m., two shots were fired from two .56 caliber pistols. Hamilton fired first, but shot into the air and through the trees, perhaps in keeping with his pre-duel pledge. Burr fired next and shot Hamilton in the abdomen. Hamilton died the next day. Indicted for murder but never brought to trial, Burr died in obscurity in 1836.

14. Turk-Jones Feud

An infamous family feud of the Ozark Mountains, the Turk-Jones rivalry began 1840 when Andy Jones and Jim Turk got into a booze-fueled fistfight that escalated into a full-on family brawl. Afterwards the grudges simmered on, and when a bounty hunter arrived in in the region looking for a kinsman of the Joneses, the Turks jumped at the chance to get revenge on their enemies. They seized said kinsman and handed him over to the bounty hunter, but the plan backfired when family patriarch Hiram Turk was charged with kidnapping. He was eventually acquitted, but shot and killed in 1841, allegedly by Andy Jones. At this point, the Turks turned their backs on the legal system and formed a vigilante band with the declared purpose of ridding their county of criminals – the Joneses and their allies obviously being numbered among these criminals.

The Turk vigilante band earned the name of “Slickers” due to their favored method of punishment, “slicking,” which entailed tying the victim to a tree and whipping him with a hickory switch. The Jones formed an alliance of “Anti-Slickers” to defend themselves and their associates, and were not above occasionally giving the Slickers a taste of their own medicine. The Turk-Jones feud died down when the Missouri government arrested 38 Slickers for attacking an innocent farmer. Even so, the concept caught on and a number of copycat Slicker groups arose in the wake of the family feud, ultimately resulting in the deaths of several innocent people.

13. Early-Hasley Feud

Born out of the aftermath of the Civil War, the Early-Hasley feud took place in Bell County, Texas, and spanned from 1865 to 1869. At the time, Union Reconstructionist forces, some of whom abused their powers and mistreated local residents, occupied the area. The feud between the Early and Hasley families began when John Early, a soldier in the Home Guard, abused an elderly man named Drew Hasley. When Hasley’s son Sam returned home from fighting with the Confederate Army, he was incensed to hear of Early’s cruelty toward his aged father. Gathering a band of relatives and family friends, including known outlaw Jim McRae, Sam Hasley resolved to take vengeance on Early and the occupying Federal forces.

It wasn’t long before the Hasley group was openly opposing Union authority and policies in the area. Early and the Yankee officials who supported him accused Hasley and his companions of various crimes, and Yankee soldiers ambushed and killed McRae in 1869. The Hasley gang broke up shortly thereafter, but one rogue member pursued Early-supporter Dr. Calvin Clark into Arkansas and killed him. In 1889, a drunken Hasley was shot to death while resisting arrest.

12. Horrell-Higgins Feud

The five Horrell brothers were notorious outlaws of the Old West, who returned – minus one fallen brother – to their hometown of Lampasas, Texas in 1874 after a yearlong crime spree. John “Pink” Higgins was a cowboy and gunman and a member of the Law and Order League, a group formed to battle horse and cattle theft. As such, he was perhaps destined to butt heads with the Horrell boys, whom he accused of cattle rustling. The local jury acquitted the Horrell brothers, but several years later Higgins shot and killed Merritt Horrell in a saloon gunfight. The three surviving brothers publicly swore revenge on Higgins, his friend Bill Wren and his brother-in-law Bob Mitchell.

On June 7, 1877, Higgins, Wren, Mitchell, and another brother-in-law, Ben Terry, rode into Lampasas and found the Horrell brothers and several of their friends gathered in the town square. Who fired first is a question that has never been satisfactorily answered, but when the smoke cleared, Wren was wounded, Mitchell slain and Horrell supporters Buck Waltrop and Carson Graham also dead. Days later the Texas Rangers swept into town, arresting all three Horrells. Texas Ranger John B. Jones mediated the dispute, which effectively ended. Two of the Horrell brothers were arrested again less than a year later, then murdered by vigilantes while confined in jail. Suspicions fell on Higgins for the instigation of the killings, but nothing was ever proven.

11. Brooks-McFarland Feud

The Brooks-McFarland feud spanned from 1896 to 1902, with most of the violence taking place in the Creek nation of Indian Territory, in what is now Oklahoma. The feud began when Thomas Brooks was shot and killed attempting to rob a former Texas Ranger. The Brooks blamed theMcFarlands for Thomas’s death, with Brooks family patriarch Willis Brooks claiming that Jim McFarland had enticed Thomas to commit the crime and then tipped off the ranger. The McFarlands denied the charge, and the argument escalated to the point where the two families vowed to shoot one another on sight.

A series of confrontations culminated in the famous gunfight at Spokogee in September 1902. Willis Brooks and his son Clifton were both killed, along with McFarland family ally George Riddle. The shootout’s survivors were arrested but promptly released on bail, and the feud finally came to its end one month later when Jim McFarland was ambushed and killed outside his home. The Brooks-McFarland conflict was one of the last great feuds in American history.

10. Reese-Townsend Feud

The blood feud between the Reese and Townsend factions of Columbus, Texas took place during the twilight of the Wild West. In 1898, former U.S. senator Mark Townsend was the undisputed powerbroker in Columbus politics, and his backing was necessary for election as sheriff in the town. Townsend withdrew his support from incumbent sheriff Sam Reese in favor of former deputy sheriff Larkin Hope, setting the stage for the feud.

At any rate, Hope never reaped the benefits of Townsend’s support. He was assassinated in downtown Columbus prior to the election. Suspicious fingers were immediately pointed in Reese’s direction, but if Reese was indeed guilty, his crimes were in vain, since Townsend’s handpicked replacement candidate William Burford won the election. In 1899, Reese provoked a gunfight with Townsend’s allies and was killed. Reese’s family swore to avenge him, and between May 17, 1899 to May 17, 1907, five shootouts in the Columbus area took the lives of four more men, including Sam’s brother Dick Reese.

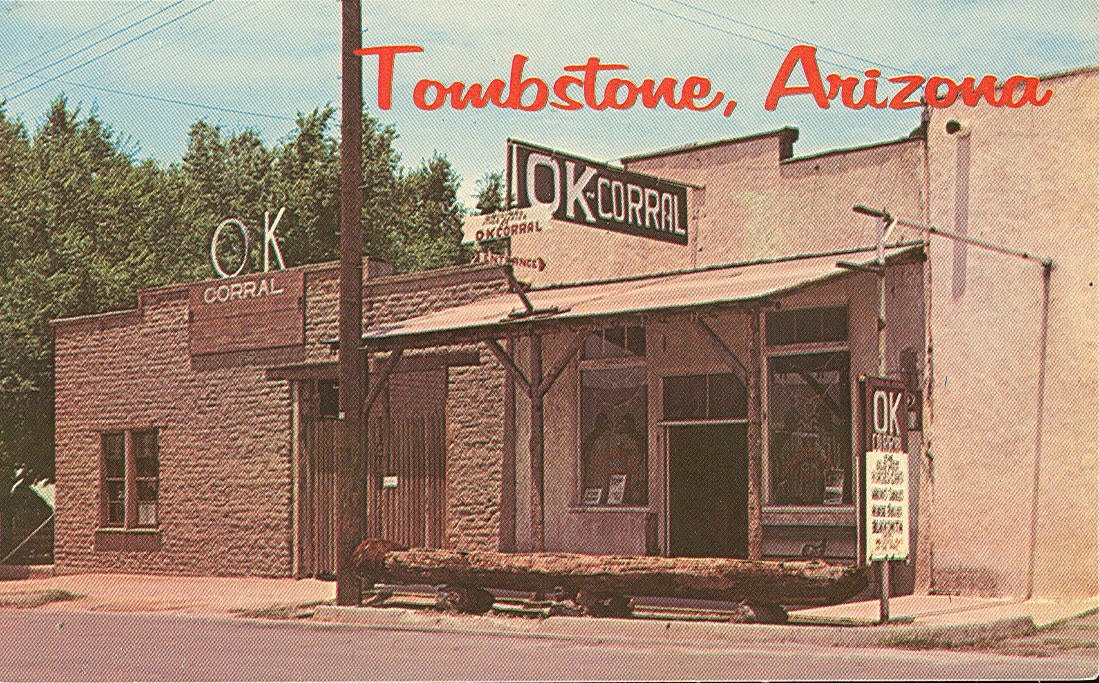

9. Earp-Clanton Feud

Probably the most famous gun battle of America’s Wild West, the shootout at the O.K. Corral was itself the deadly climax of a bitter family feud. Members of the tight-knit Earp family had served together as marshal, deputy marshal and sheriff in various towns. In Tombstone, Arizona, the Earps, who where native Northerners and Republicans, soon butted heads with a local faction known as the Cowboys, who were known to be less than scrupulous about exactly who owned the cattle and horses they herded and who had the support of the local sheriff. The Cowboys were mostly southern Democrats and Confederate sympathizers. Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy and Ike Clanton, members of the Cowboy faction, were particularly in conflict the Earps.

After a series of complicated confrontations involving smuggling, stage robberies, U.S.-Mexican relations and an election for sheriff, the wheels were set in motion for a final showdown when sheriff-candidate Wyatt Earp allegedly tried to make a deal with Frank McLaury and Ike Clanton in exchange for the whereabouts of three stagecoach robbers. As the deal fell apart, Ike accused Earp of leaking secrets to heavy-drinking dentist Doc Holliday. Outraged by the accusation, Holliday threatened to take on Ike Canton in a gunfight. On the 26th of October he made good on his word. As the town buzzed in anticipation of the showdown, the Earps congregated in front of a corner saloon, watching as Ike Clanton and Billy and Frank McLaury bought ammunition from a nearby gun shop.

The notorious gunfight began around 3:00 in the afternoon, with the two opposing parties standind about six feet away from one another. Within thirty seconds, about thirty shots had been fired. There are many conflicting versions of what exactly happened that fateful afternoon, but when the smoke cleared, Doc Holliday along with Earl, Wyatt and Virgil Earp were left standing, while Billy Clanton, Frank McLaury and Tom McLaury lay dead in the dirt. Although not especially big news at the time, the story was later immortalized by Hollywood.

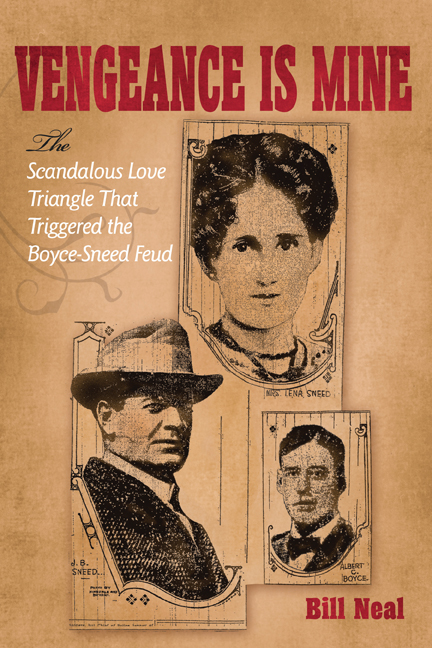

8. Boyce-Sneed Feud

An early twentieth-century feud with a death toll of eight, the Boyce-Sneed feud was a conflict between two wealthy cattle ranchers, John Beal Sneed and Albert Boyce, Jr. This was an honor feud with a woman behind it. In late 1911, after over a decade of marriage and two daughters, Lena Sneed broke the news to her husband that she had been having an affair with Boyce, and asked for a divorce. Appalled, Sneed had his wife committed to an asylum, but Boyce “rescued” his lover and fled with her to Canada. Sneed called the police, and Boyce was initially charged with kidnapping, but after the charges were dropped, an outraged Sneed determined to take justice into his own hands.

In 1912, Sneed fatally shot the unarmed Albert Boyce, Sr. in the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel. In a highly sensationalized court proceeding, Sneed’s legal team secured a mistrial ruling. When the news got out, an angry mob attacked the courthouse, and four men were killed in the attack. Shortly thereafter, Sneed’s father was killed in a murder-suicide. In September 1912, a disguised Sneed shot and killed Boyce, Jr. in the streets, then surrendered himself at the local courthouse. Sneed, who had since reunited with Lena, was eventually acquitted of both killings, with the juries declaring both shootings justifiable homicides.

7. The Regulator-Moderator War

The first major feud in Texas history was the Regulator-Moderator war that ravaged Texas’s Shelby and Harrison counties, an anarchic hotspot for cattle rustling and land fraud. One such land fraud led to a dispute between Joseph Goodbread and Sheriff Alfred George, who summoned fugitive riverboat captain Charles W. Jackson to his aid. Jackson’s solution was to shoot and kill Goodbread. Jackson was the leader of a vigilante band known as the Regulators, who were already in conflict with a counter-vigilante group called the Moderators. When Jackson was scheduled to stand trial before a known Moderators supporter, the vigilante captain’s friends showed up at the courthouse armed to the teeth, causing the terrified judge to flee. Wielding their own brand of justice, the Moderators ambushed and killed Jackson and an innocent bystander.

The Regulators retaliated by burning down the homes of Moderator-affiliated families and surprise-attacking Jackson’s assassins. The feud’s biggest battle took place when 225 Moderators attacked 62 Regulators near the town of Shelbyville. By 1844, Sam Houston had resolved to put an end to the violence. He rode into East Texas with a militia, and the two factions agreed to disband. Veteran vigilantes from both sides soon put their pistol-wielding proclivities to use in the Mexican War.

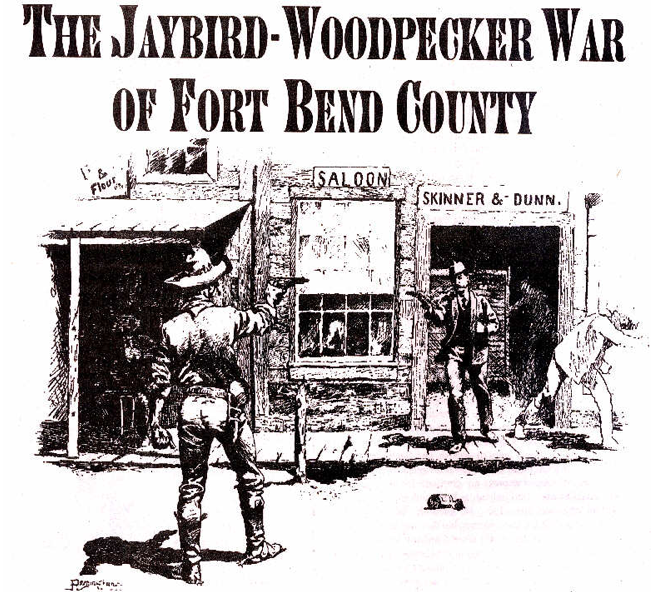

6. Jaybird-Woodpecker Feud

The Jaybird-Woodpecker feud, a politically motivated conflict set in Fort Bend, Texas against the backdrop of the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, got its name from the songs sung by a local African-American man. The “Woodpeckers” were the members of Fort Bend’s Reconstruction-supporting Republican government, which was largely backed by black voters. The “Jaybirds” were white Democrats who opposed the Republican Party. The feud began after Fort Bend’s 1888 election, which was supervised by the Texas Rangers and which saw each and every one of the Republican Woodpecker candidates elected or reelected.

There had been several confrontations between factions during the campaigning season, but the conflict truly heated up following the election, when a Woodpecker tax assessor killed a Jaybirds leader. The feud culminated with the Battle of Richmond on August 16, 1889. Centered around the town courthouse and hotel, the battle began with an exchange of shots and lasted for about 20 minutes, resulting a number of casualties. Martial law was declared and the governor of Texas arrived the following day to mediate the dispute.

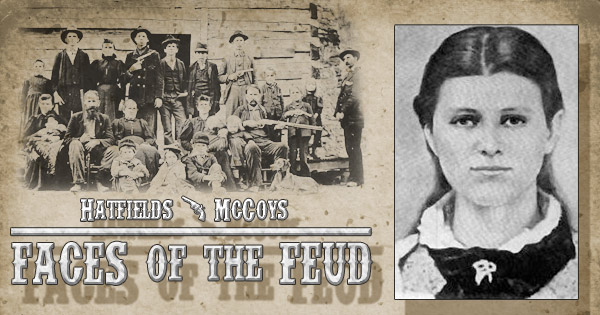

5. Hatfield-McCoy Feud

The most famous blood feud of them all, the decades long violence between the Hatfield and McCoy families of West Virginia and Kentucky is an iconic part of American history and legend. Problems between the two clans began in 1865, when Asa McCoy, a former Union soldier, was gunned down and killed by a group of Confederate irregulars, with several Hatfield associates among them. Thirteen years later, violence broke out again over a court case involving the ownership of a stray pig. Two McCoys killed a witness who testified against them, though this witness actually happened to be related to both families.

Given the bad blood between them, neither clan was particularly pleased when Roseanna McCoy began a relationship with Johnson “Johnse” Hatfield — but the things got especially ugly when Johnse abandoned the now-pregnant Roseanna. In 1882, three of Roseanna’s brothers killed Johnse’s uncle Ellison, stabbing him 26 times and then topping it off with a bullet to the chest. The next day, as the McCoy brothers were being escorted to Kentucky for arraignment, the Hatfield clan intercepted them, took them captive, tied them up and killed them.

Things came to a standstill for awhile, but when the government began arresting Hatfields, the clan felt the need to do away with pater familias Ranel McCoy, to keep him from testifying against them in court. On New Year’s Day, 1888, the Hatfields surround Ranel’s cabin and set fire to the place, then fired some shots. Two McCoy’s were killed and Mrs. McCoy beaten, but Ranel escaped to a nearby pigpen. After this, there were sporadic episodes of further violence, and by the time feud finally died down, the death toll numbered at about a dozen.

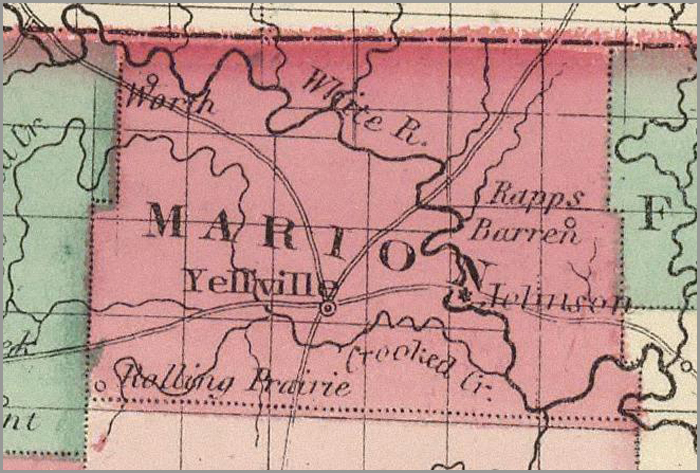

4. Tutt-Everett Feud

Largely motivated by political fighting, the Tutt-Everett feud took place in Marion County, Arkansas, in the years leading up to the Civil War. The Tutt family members belonged to the Whig Party, while the Everett clan gave allegiance to the Democratic Party. The violence began with a brawl during a political debate. In 1848, the feud’s first gunfight took place, and John Everett was the feud’s first casualty. The Everetts soon retaliated by killing two Tutt family allies. Several more gunfights of increasing size and deadliness followed, one of which involved the local sheriff and his posse. Eventually the governor of Arkansas dispatched a militia to calm things down. Several Everetts were jailed but freed by friends. When Jesse Everett killed Hamp Tutt in 1850, the feud effectively ended.

3.Sutton-Taylor Feud

In a state with more than its fair share of blood feuds, the Sutton-Taylor feud is known as the longest-lasting and widest-spread in Texas history, costing the lives of at least 35 men. In Dewitt County, deputy sheriff William Sutton found it necessary to shoot and kill three members of the Taylor clan within a one-year span. A year later, Sutton was sent to arrest two in-laws of the Taylors on a minor charge, but the arrest ended with both of the suspects dead. “Who sheds a Taylor’s blood, by a Taylor’s hand must fall” became the Taylor family motto, and the violence began in earnest after the Taylors killed two Sutton allies.

The feud between the Taylor family and the Sutton faction led to mobs, prison breaks, ambushes and lynchings. Famed outlaw John Wesley Hardin eventually got involved on behalf of the Taylors. After failed attempts at truces and peace treaties, two Taylors gunned down Sutton on a steamboat platform, where Sutton had been waiting for a boat in the hopes of leaving Dewitt County and the feud behind for good. Even after Sutton’s death, fighting between the two factions continued sporadically until the Texas Rangers finally put an end to the conflict in 1877.

2. Lee-Peacock Feud

The Lee-Peacock Feud was not so much a feud as a continuation of the Civil War. In the Corners region of northeast Texas, Confederate veteran Bob Lee had a falling out with officials of the Union League, an organization for Union sympathizers that had set up headquarters a few miles from Lee’s home. Union League leader Lewis Peacock and a posse of his supporters responded by riding to Lee’s home and “arresting” him for alleged crimes committed during the War, seizing some valuables and forcing Lee to sign a promissory note for $2,000. Lee brought a suit for extortion against Peacock and won the case.

Shortly thereafter, an assassination attempt was made on Lee. The attempt failed, but a Peacock-supporter murdered Lee’s doctor while Lee lay convalescing from his wound. Lee and Peacock both formed bands of supporters and began a bloody conflict that took the lives of as many as 50 men. By 1868, things had gotten so out of hand that the Union League requested help from the Federal Government. Finally, the Fourth United States Cavalry rode out to settle the matter. Their house-to-house search for Lee spurred several further gun battles. Lee was ultimately betrayed by one of his own men, and was shot down by cavalry soldiers on May 24, 1869. Still, the fighting did not cease completely until Peacock was killed in June 1871.

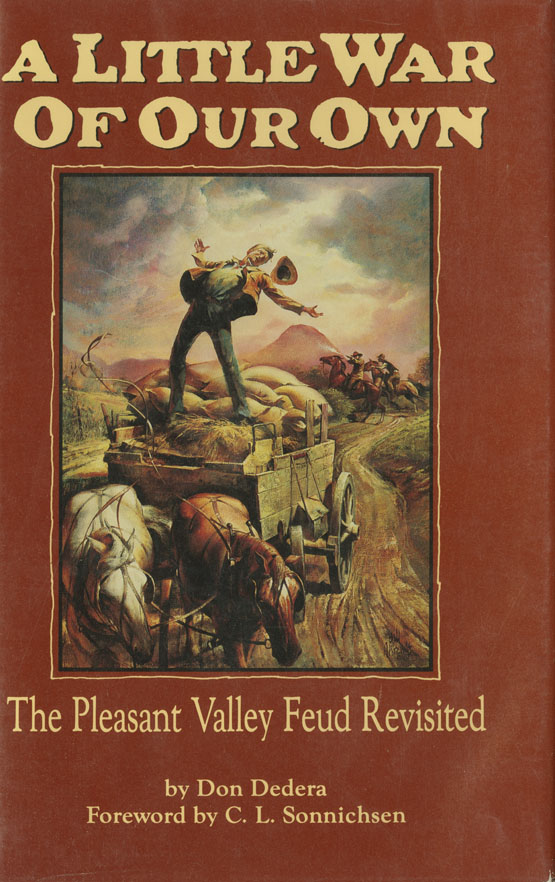

1.Graham-Tewksbury

Though the enmity between them evgraham entually turned into one of the bloodiest feuds in U.S. history, the Graham and Tewksbury clans started out as allies and business partners. That business happened to be the rustling of cattle in Pleasant Valley, Arizona, and it was likely an argument over some of the stolen livestock that sparked the feud, though Tewksbury’s were also accused of allowing their sheep to over-graze local land. In 1887, the Grahams decided they couldn’t take it anymore, and Thomas Graham shot a Tewksbury hired hand caught herding the family’s sheep on contested fields. Ed Tewsbury avenged his fallen comrade by shooting Thomas Graham, and then went into hiding. The Grahams organized a raid party and surrounded the Tewksbury homestead, and the ensuing siege lasted for several hours. A brief ceasefire was held for Mrs. Tewksbury, allowing her attend to the bodies of her slain son John and his friend William Jacobs.

As the feud continued over several years, an estimated 20 to 50 men were killed. Attacking parties usually wore masks, making it difficult to bring any of the perpetrators to justice. The feud did not end until 1892, when the last surviving scions of each family at last met their destinies in Tempe. Fugitive Ed Tewksbury shot and killed Thomas Graham, Jr., spilling the last of the Graham blood. Tewsbury was tried and convicted, but his case was dismissed due to a legal technicality, and he died of natural causes in 1904. This bitter feud wreaked consequences beyond those endured by the two families. At the time of conflict, Arizona was making its bid for statehood, but many legislators in Washington pointed to the unfettered violence between Grahams and Tewksbury as proof that Arizona was not yet civilized enough to join the Union. Some historians argue that the feud may have set Arizona’s statehood back by years if not decades.

Follow

Follow